Introduction

The skill of rhetoric and the pursuit to achieve it has been one of the most coveted in all of recorded human history perhaps only secondary to the pursuit of love and happiness, or to find the meaning of life. From every powerful men who have conquered various corners of the earth to the witches who have seduced them, rhetoric has been at the core of their success. If it wasn’t for the idea and the study of rhetoric, the Socratic Dialogues or Homer’s Iliad may have no influence on us today, and the geo-political boundaries may look completely different. It is of no surprise that the study and the pursuit of masterful rhetoric in music in both its composition and performance is highly sought after. In this paper, we will examine various ideas about rhetoric and its building blocks.

Rhetoric in the simplest sense is the art or the craft of persuasion or discourse. It is defined in the New Oxford American Dictionary as “the art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing, esp. the use of figures of speech and other compositional techniques.”1 For us in the study of musical rhetoric, the last part is often the most useful area of study where the aim is to understand the effective use of figures in musical gestures and communication.

Earliest studied examples of rhetoric as a form of craft come back from the surviving manuscripts of the Old Israelites and Old Babylonian Mesopotamia in languages such as Akkadian (also commonly referred to as Assyro-Babylonian). Akkadian—the first documented language in the family of languages including Arabic and Hebrew—was the first to demonstrate the concept of rhetoric and its importance.2 This spread to other cultures such as Egyptians where the skill in eloquence and discourse was highly regarded and valued. Its importance and value then spread to all over the earth to the teachings of Jesus Christ, the words of Confucius, traditions of Tao, and many more.

In music, there are two distinct ways in which we can study rhetoric. The first way is in the figures themselves. This is the compositional aspect of studying a figure in its form or structure. Such observations can be somewhat strict and formulaic. The second area of study is how those figures interact in what one might consider musical dialogue. This sort of musical rhetoric through dialogue contain other subjects of musical study such as counterpoint and voice leading. In this branch of musical rhetoric, one might discuss the ways in which different fugal subjects interact in dialogue with each other.

Figures As Rhetoric

In the highly fictionalized movie Amadeus, Salieri begs the question of just how Mozart was able to write all of those unforgettable melodies. At several points in the movie, Salieri compares Mozart to God himself by saying such things as “that was not Mozart laughing, Father… that was God.” It is widely agreed that Mozart was a gifted composer beyond anyone’s imagination. As elusive as his compositional inspiration might be, there are some observations that we can make from his music by drawing parallels to devices of rhetoric in literature to help us understand why it is so compelling or convincing to the listener.

Let’s take the melody of the 40th symphony which is nearly synonymous with the name of Amadeus Mozart himself:

This is an example a tricolon which is defined as “three parallel elements of the same length occurring together in a series.”3 A great example of this figure is the famous quote from Julius Caesar: “Veni, vidi, vici.” Translated as “I came, I saw, I conquered,” its form is a powerful one that will get reused continuously throughout history to pronounce something powerful or authoritative. Each of these tricolons also happens to be a hendiatris which is a rhetorical figure of speech where three words or phrases are put together to refer to the same object or idea.4 This comes together to form a string of words and ideas becoming this iconic melody.

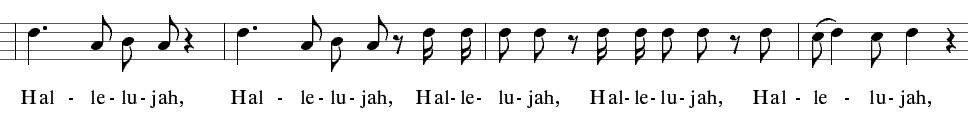

Another very common rhetorical device is something we call the sentence structure when analyzing melodies. Sentence structure, which can be summed up as AAB, is analogous to the rhetorical device named an epizeuxis. Defined as the “repetition of words with no others between, for vehemence or emphasis,” it is one of the most common devices in all of literature. It can be seen in the most powerful moments in Shakespeare (“O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”) to the most cheerful of holiday music in Jingle Bells (“Jingle Bells, Jingle Bells, \ Jingle all the way.”) or to various parts of Messiah. The old “knock knock” jokes are also based on this rhetorical device.

The epizeuxis device is evident in the melodic line, not the text.

The epizeuxis device is evident in the melodic line, not the text.

There are enough of these rhetorical devices to make a book full of their definitions and examples. However, the most important thing is to understand that literature, music, and popular culture all share these common rhetorical devices that seem intrinsic to the human mind.

Dialogue as Rhetoric

When Alex Ross, the music critic for the New Yorker, says that Lindberg’s Kraft showed “extroverted rhetorical flair,”5 he means that the performance itself was full of clear rhetoric and dialogue. There are many ways in which a performance can be considered rhetorical, but unlike figures as rhetoric, this one is more subjective and open to interpretation.

Because it is difficult to articulate why a performance is rhetoric, I will show an example. At this point, it would be useful to clarify that the difference between Figurenlehre and Rhetoric is very nuanced but distinct. Figurenlehre is the study of the musical content as groups notes on the page. It is studying the architecture and the structure of a piece based on its figures. The Rhetorical study aims to go deeper into the meaning and the implications of these figures. This kind of deeper study aims to answer or understand why or how the music is communicating its message with its figures.

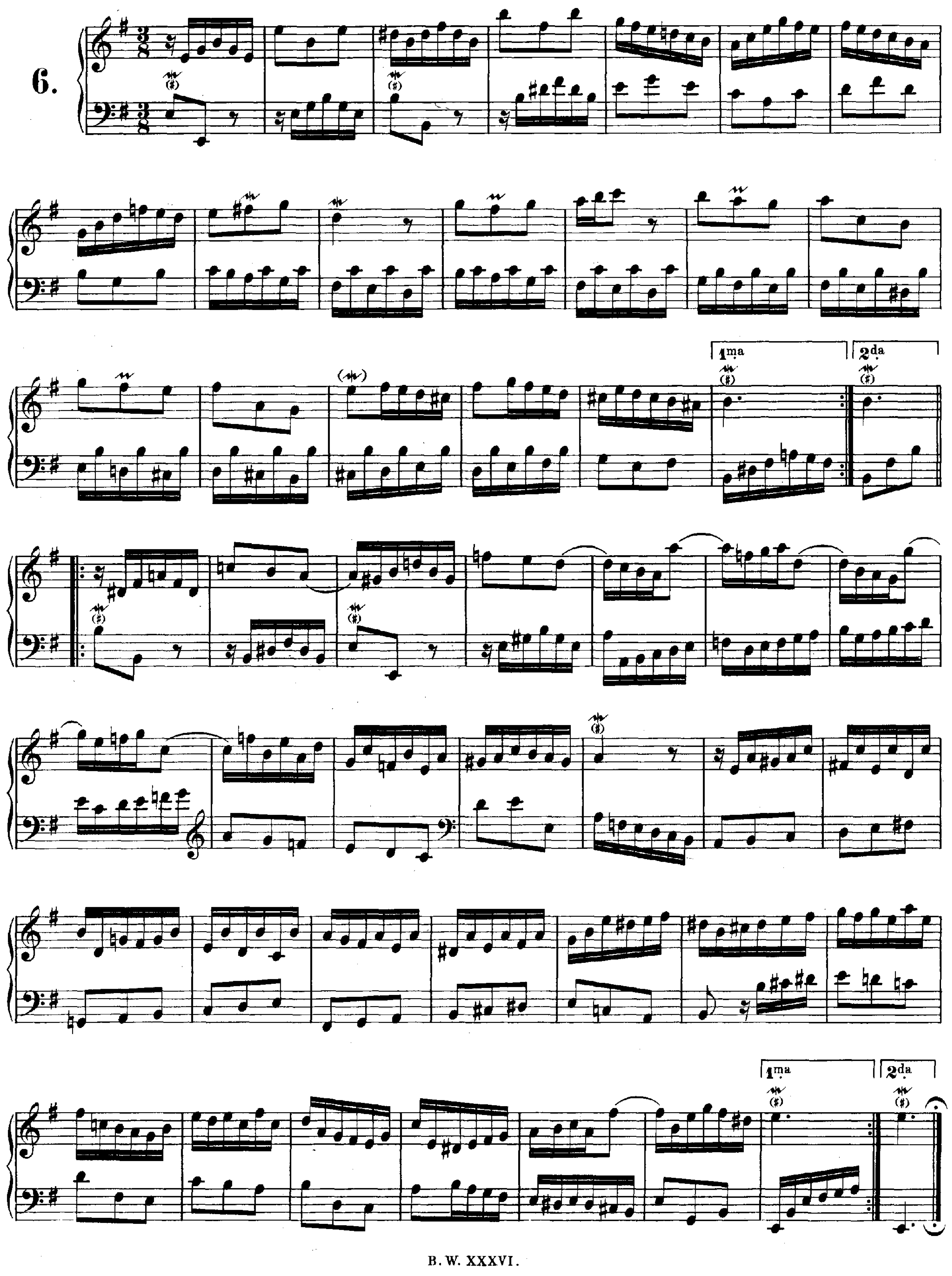

Little prelude in e minor from BWV 938 by J. S. Bach

Little prelude in e minor from BWV 938 by J. S. Bach

This prelude shows two clear voices in discourse:

As you can see, the figures alternate in each of the voices to form these four bars. Two separate ideas voiced by two separate voices. The upper voice begins with a sort of a figura suspirans. The arpeggiation comes after a quick breath which is unusual because usually a smooth or a scalar figure follows a figura suspirans, not arpeggiation. Given the arpeggiation following a figura suspirans, it suggests a loud gesture. This discourse is not your every-day chitchat. This is further evident in the second lower voice with an octave leap following a mordent. Repeating it in the dominant (rather than more music in the tonic) shows us that this entire prelude will stem from the first two measures. A good performance must capture the loud nature of these gestures as well as the figura suspirans in the rest. In addition, it must also not slur or suggest smoothing of the leaps of the octave (bass) and fourths (treble). A good player may be able to bring out the idea of the crisscrossing voices and figures suggesting a highly intense discourse.

As you can see, the figures alternate in each of the voices to form these four bars. Two separate ideas voiced by two separate voices. The upper voice begins with a sort of a figura suspirans. The arpeggiation comes after a quick breath which is unusual because usually a smooth or a scalar figure follows a figura suspirans, not arpeggiation. Given the arpeggiation following a figura suspirans, it suggests a loud gesture. This discourse is not your every-day chitchat. This is further evident in the second lower voice with an octave leap following a mordent. Repeating it in the dominant (rather than more music in the tonic) shows us that this entire prelude will stem from the first two measures. A good performance must capture the loud nature of these gestures as well as the figura suspirans in the rest. In addition, it must also not slur or suggest smoothing of the leaps of the octave (bass) and fourths (treble). A good player may be able to bring out the idea of the crisscrossing voices and figures suggesting a highly intense discourse.

In these next bars, it is highly striking that the upper voice has six-bar phrases where as the lower voice has phrases of four and eight bars long (yellow against green). In addition, the eight bar phrase is actually a six bar phrase with the first two bars repeated (beginning of the red).

It suggests that the first voice pulled a trick on the second by not staying within the standard four-bar parameter (yellow overlapping red). Therefore, the second voice has to repeat itself to respond to the first voice (beginning of the red). However the second voice continues past the first voice until the end of the section (purple on red) as a retort.

It suggests that the first voice pulled a trick on the second by not staying within the standard four-bar parameter (yellow overlapping red). Therefore, the second voice has to repeat itself to respond to the first voice (beginning of the red). However the second voice continues past the first voice until the end of the section (purple on red) as a retort.

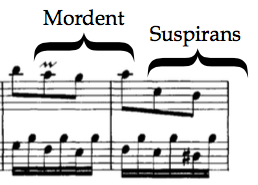

There are many musical figures present in the previous section. Although all of them can be examined in further study along with the sources in the bibliography, one we should focus on is the use of mordents. Bach uses it as both ornaments and figures:

and

and  .

.

Another important one is the figura suspirans.

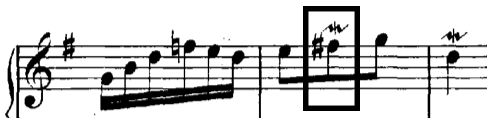

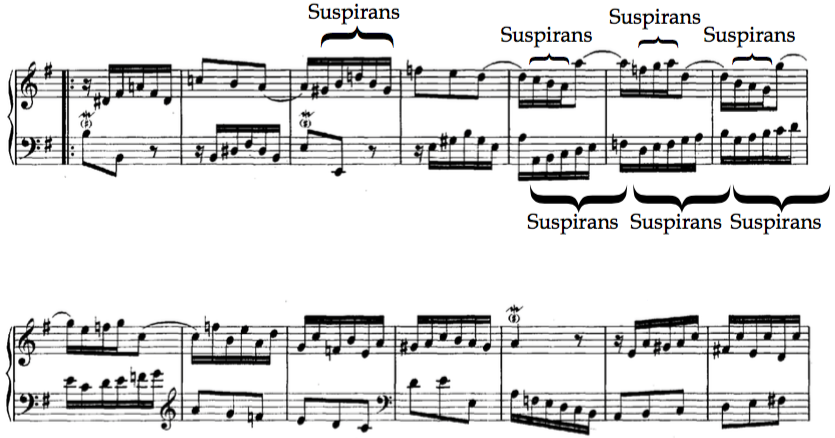

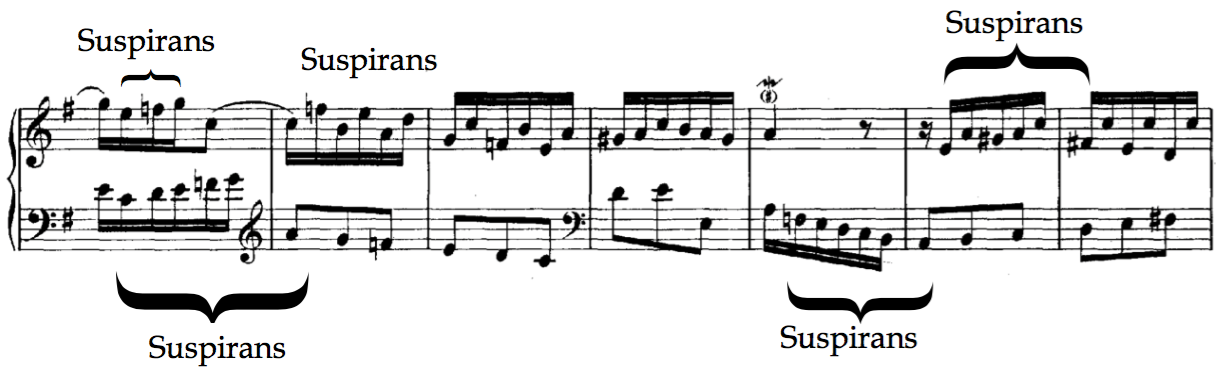

Here, the beginning of the second section:

In the second line, can you spot the suspirans obscured by notation/beaming?

Here are the suspirans in the second line:

We can begin to understand this piece better when we can perceive its rhetoric. Therefore, we can also better express its meaning and musical gestures for the benefit of the audience. In this piece, the salient feature was its “loud” gestures as evident in all of those leaps, especially the alternating fifths/fourths; the figura suspirans, which Montiverdi used “when text and melody were geared to some kind of sobbing expressiveness”;6 and the accentuating mordents both as ornaments and figures. In a sensical performance, the loudness of its gestures and the gestures themselves should be highlighted to the fullest possible extent while remaining musical.

Introductory Bibliography

Literary Rhetoric

- Burton, Gideon. Silva Rhetoricæ. Brigham Young University, 2007. http://rhetoric.byu.edu/.

- Eldenmuller, Michael. American Rhetoric. http://americanrhetoric.com/.

- Howard, Greg T. A Dictionary of Rhetorical Terms. Xlibris Corporation, 2010.

- Lanham, Richard. A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms. University of California Press, 2012.

Musical Discussions of Rhetoric

- Bartel, Dietrich. Musica Poetica: Musical-Rhetorical figures in German Baroque Music. University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

- Beghin, Tom. Haydn and the Performance of Rhetoric. University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Blake Wilson, et al. “Rhetoric and music.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- Harnoncourt, Nikolaus. Baroque Music Today: Music As Speech: Ways to a New Understanding of Music. Amadeus Press, 1995.

- ————. The Musical Dialogue: Thoughts on Monteverdi, Bach and Mozart. Amadeus Press, 2003.

- Haynes, Bruce. The End of Early Music: A Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Keller, Herrmann. Phrasing and Articulation; A Contribution to A Rhetoric of Music, with 152 Musical Examples. Norton, 1965.

- Ratner, Leonard. Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style. Schirmer Books, 1985.

- Rumph, Stephen C. Mozart and Enlightenment Semiotics. University of California Press, 2011.

- Schulenberg, David. “Musical Expression and Musical Rhetoric in the Keyboard Works of J. S. Bach.” Johann Sebastian: a Tercentenary Celebration, ed. S.L. Benstock. West Port, CT, 1992.

- Tarling, Judy. The Weapons of Rhetoric: A Guide for Musicians and Audiences. Corda Music, 2004.

- Williams, Peter. “Figurenlehre from Monteverdi to Wagner.” The Musical Times. Vol. 120, No. 1636 to 1640. (Four part series spread out several issues).

-

New Oxford American Dictionary, 3rd edition by Oxford University Press, 2012. ↩︎

-

William W. Hallo, “The Birth of Rhetoric,” Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks, Carol S. Lipson and Roberta A. Binkley, editors, State University of New York Press, 2004, pg. 25 ↩︎

-

Gideon O. Burton, “Tricolon,” Silva Rhetoricæ, Bringham Young University, http://rhetoric.byu.edu/figures/T/tricolon.htm ↩︎

-

Gregory T. Howard, “Hendiatris,” Dictionary of Rhetorical Terms, XLibris Corporation, 2010, pg. 115. ↩︎

-

Alex Ross, “Aldeburgh 1995,” The New York Times, July 2, 1995, accessed from his blog at http://www.therestisnoise.com/2006/07/aldeburgh_1995.html ↩︎

-

Peter Williams, “Figurenlehre from Monteverdi to Wagner 3: The Suspirans,” The Musical Times, Vol. 120, No. 1638 (Aug., 1979), pp. 648-650. ↩︎