Program notes written for Vanderbilt Commodore Orchestra’s concert on January 30, 2016.

Polovtsian Dances

Alexander Borodin is one of the most interesting composers. He was not only a widely respected organic chemist in his day (he is co-credited with the discovery of the Aldol reaction) but he also composed one of the most famous Russian operas (Prince Igor), adopted children, and was an activist for women’s rights (especially in equal education). In pursuit of that cause, he founded the School of Medicine for Women in St. Petersburg. He died while apparently having too much fun dancing at a ball before being able to complete Prince Igor, a side project he had been working on-and-off for the last 18 years of his life.

The name “Polovtsian” comes from the old Russian word for the nomadic tribes of the Eurasian steppe in the 11th and 12th centuries. The Eurasian steppe is the stretch of temperate grasslands from western Hungary all the way to eastern China and North Korea along the southern border of Siberia. As the 17th number of Prince Igor, Borodin’s diverse musical ideas depict the Polovtsian slaves dancing and singing for Konchak (a Polovtsian ruler) and his prisoner, Prince Igor, at the end of Act 2.

Slavonic Dances, Op. 46

Inspired by Brahms’ Hungarian Dances, Dvořák’s first set of Slavonic Dances launched his career into the international stage. Dvořák was relatively unknown outside of Bohemia prior to composing these dances, which was commissioned by Fritz Simrock (Brahms’ own music publisher) in 1878.

The Furiant is a quick and brilliant Bohemian dance, often used by Czech composers such as Dvořák. Of its many quirky features, the two most prominent are its off-beat accentuations and its fluidity between being felt in two or three.

The Sousedská (pronounced “sow-sedhs-ka”) is a slow Bohemian dance for a couple. Its gentle motions felt in threes are a big contrast to the furiant.

The famous Polka originates from 19th century Central Europe where it still remains popular. While the origin of the word polka itself is widely debated, the Czech word “půlka” (pronounced “poo-ool-ka”), meaning “half,” gives a good idea of this dance’s fun short half-steps.

The Skočná (pronounced “scohtch-naw”) is a fast folk dance felt in two. This simple Slavic dance is a fun group dance.

Hungarian Dances

The Hungarian Dances is one of Brahms’ most popular works. Interestingly, it is also one of the least original as only three of the dances are totally new. All the other dances are based on preexisting musical materials such as a traditional folksong. Brahms originally wrote these 21 dances as a piano duet, but orchestrated (arranged for a full orchestra) a few himself, including No. 3. Albert Parlow (1824-1888), a composer and conductor in the Prussian Army, orchestrated the other two dances you will hear this evening.

Ballet Suite from Le Cid

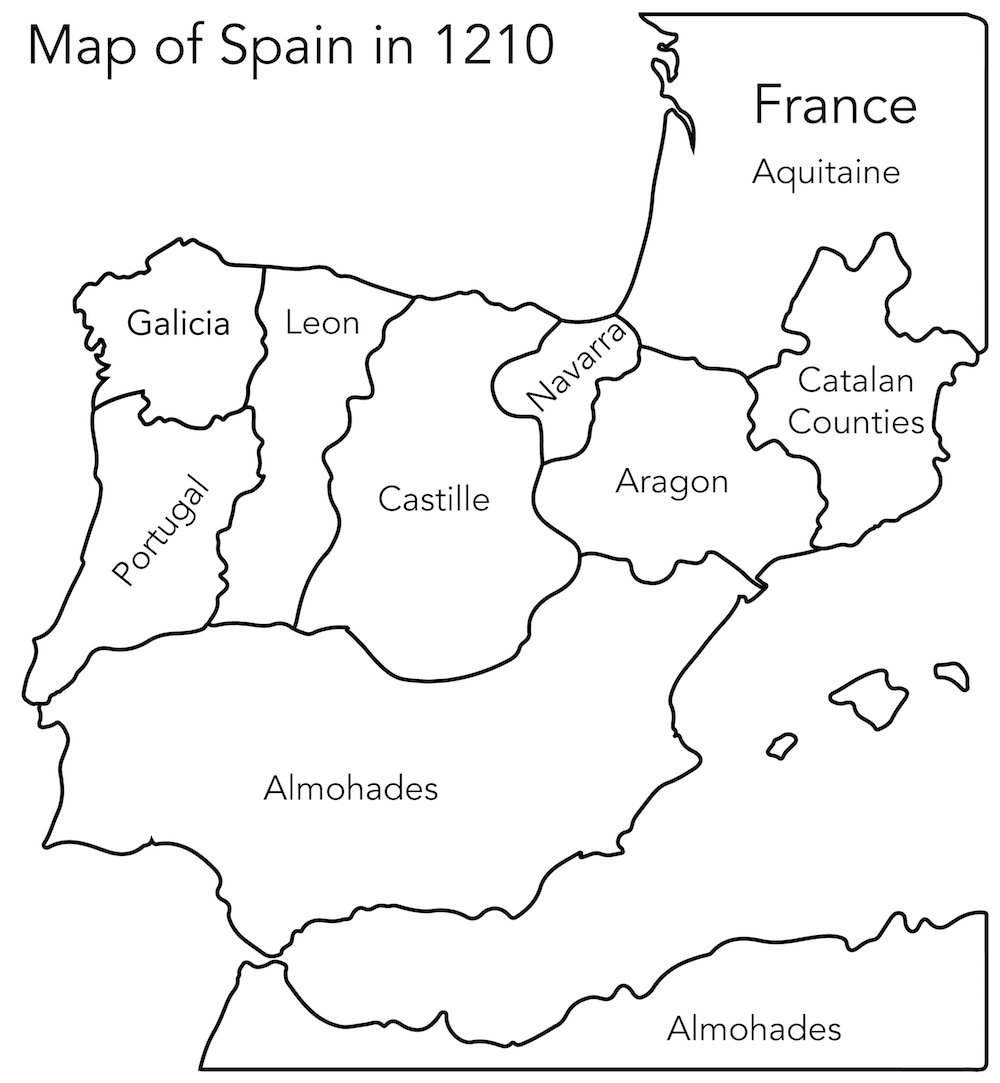

By popular demand, most Parisian operas from the mid-1800s contained a lightweight ballet to balance out the intense drama of the opera itself. For Massanet, these diversionary intermezzos often became more famous than the operas themselves. This was the case for the Spanish-Moorish epic, Le Cid. Its ballet suite captures the local dances of many different parts of Spain.

Not shown on the map is Andalouse. The modern Andalusia lies on the South Eastern portion within the Spanish side of the Almohades region shown above.

Interestingly, “Aubade”—the only movement not derived from a regional dance—is a morning love song about two lovers separating at dawn. Here is an example of an Aubade by John Dunne:

THE SUN RISING

by John Donne

Busy old fool, unruly sun,

Why dost thou thus,

Through windows, and through curtains call on us?

Must to thy motions lovers' seasons run?

Saucy pedantic wretch, go chide

Late school boys and sour prentices,

Go tell court huntsmen that the king will ride,

Call country ants to harvest offices,

Love, all alike, no season knows nor clime,

Nor hours, days, months, which are the rags of time.

Thy beams, so reverend and strong

Why shouldst thou think?

I could eclipse and cloud them with a wink,

But that I would not lose her sight so long;

If her eyes have not blinded thine,

Look, and tomorrow late, tell me,

Whether both th' Indias of spice and mine

Be where thou leftst them, or lie here with me.

Ask for those kings whom thou saw'st yesterday,

And thou shalt hear, All here in one bed lay.

She's all states, and all princes, I,

Nothing else is.

Princes do but play us; compared to this,

All honor's mimic, all wealth alchemy.

Thou, sun, art half as happy as we,

In that the world's contracted thus.

Thine age asks ease, and since thy duties be

To warm the world, that's done in warming us.

Shine here to us, and thou art everywhere;

This bed thy center is, these walls, thy sphere.

About the Conductors

Jeremy Wilson is Associate Professor of Trombone at Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music. Prior to his appointment at Blair in 2012, he spent five years as a member of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and its sister organization, the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera. Wilson performed as guest principal trombonist with the Nashville Symphony Orchestra during their 2013-14 classical series, and has also performed with the Saito Kinen Festival Orchestra and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He holds degrees from the University of Tennessee and the University of North Texas, and is in his first season as Music Director of the Commodore Orchestra.

Keehun Nam recently graduated from the Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt as a Bachelor of Music cum laude. When not working at the Blair School of Music as a Teaching Assistant in Music Theory or Accompanist for the advanced conducting course, he is preparing for further studies in Orchestral Conducting at a graduate school. He is thankful for all the opportunities afforded at the Blair School of Music and Vanderbilt University at large. He is especially thankful for Robin Fountain and Dean Mark Wait for their support of his studies in conducting as well as their commitment to the success of the Commodore Orchestra.